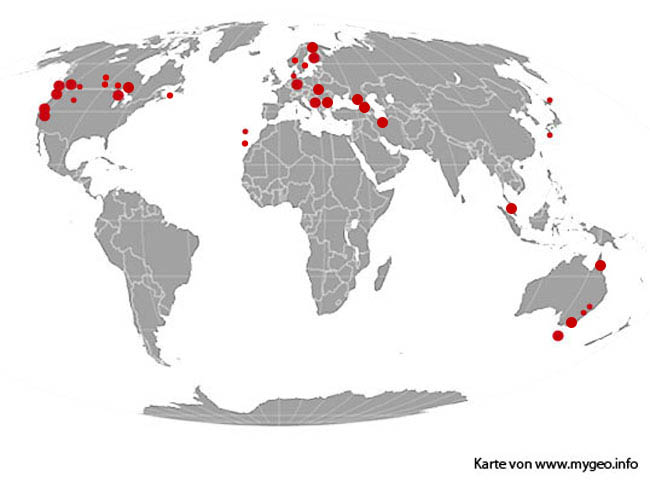

- AUSTRALIA: NEW SOUTH WALES

- AUSTRALIA: QUEENSLAND

- AUSTRALIA: TASMANIA

- Evercreech Forest Reserve

- Franklin-Gordon Wild Rivers National Park

- Lower Coles Road

- McDougall’s Road

- Reynold Falls Nature Recreation Area

- Styx Tall Trees Forest Reserve

- Tarkine

- AUSTRALIA: VICTORIA

- AUSTRIA

- BOSNIA-HERZEGOVINA

- BULGARIA

- Baiuvi dupki-Dzhindzhiritsa Nature ReserveNEW

- Boatin Strict Nature Reserve - NEW !!

- Dzhendema Strict Nature Reserve - NEW !!

- Parangalitsa Strict Nature Reserve - NEW !!

- Rila Monastery Forest Reserve - NEW !!

- Steneto Strict Nature Reserve - NEW !!

- CANADA: ALBERTA

- CANADA: BRITISH COLUMBIA

- Carmanah Walbran Provincial Park

- Clayoquot Sound Biosphere Reserve

- Glacier National Park

- MacMillan Provincial Park

- Pacific Rim National Park Reserve

- Yoho National Park

- CANADA: NOVA SCOTIA

- CANADA: ONTARIO

- Lake Superior Provincial Park

- Michipicoten parks

- Quetico Provincial Park

- Rainbow Falls Provincial Park

- CANADA: SASKATCHEWAN

- CROATIA

- CZECHIA

- DENMARK

- FINLAND

- Helvetinjärvi National Park

- Isojärvi National Park

- Kurjenrahka National Park

- Patvinsuo National Park

- Petkeljärvi National Park

- Pyhä-Häkki National Park

- Urho Kekkonen National Park

- Vätsäri Wilderness Area

- GEORGIA

- GERMANY

- Bavarian Forest National Park

- Fauler Ort Nature Reserve

- Hainich National Park

- Harz National Park

- Heilige Hallen Nature Reserve

- Jasmund National Park

- Müritz National Park

- Rhön Biosphere Reserve

- IRAN

- JAPAN

- MONTENEGRO

- PORTUGAL

- ROMANIA

- SLOVAKIA

- Boky National Nature Reserve

- Dobroč National Nature Reserve

- Havešová National Nature Reserve

- Stužica National Nature Reserve

- SPAIN

- SWEDEN

- UNITED STATES: CALIFORNIA

- Humboldt Redwoods State Park

- Kings Canyon National Park

- Mokelumne Wilderness

- Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park

- Sequoia National Park

- Yosemite National Park

- UNITED STATES: MICHIGAN

- UNITED STATES: WASHINGTON

- Goat Marsh Research Natural Area

- Mount Rainier National Park

- Olympic National Forest

- Olympic National Park

- UNITED STATES: WYOMING

Daintree National Park, Queensland, Australia

This famous park (1200 km 2 ) includes the biggest area of tropical rainforest in Australia. The park is divided in two parts, the northern one consisting of coast and coastal mountains and the southern one a mountainous region further from the coast. The park is mostly inaccessible – there are no trails and the slopes are steep. The park is a part of the Wet Tropics of Queensland World Heritage Site. Though almost all of the accessible rainforests were selectively logged before the creation of the World Heritage Site 1 , there has been no cutting of trees for shifting cultivation as Australian aboriginals were not farmers 2 .

The tree flora of the whole Wet Tropics region consists of more than a thousand species

3

, the greatest diversity being in small trees

4

. 40–166 tree species can be found per hectare

4 5 6

which approximates the global average for tropical rainforest

7

. Species identification is challenging, but there is an excellent identification guide

3

. The floristic composition at different locations, even within the same forest type, can be very distinct

8

, so that forests cannot be classified by species composition only

9

. The most abundant rainforest tree genera of Daintree National Park include

Syzygium

and

Lindsayomyrtus

(Myrtaceae),

Cryptocarya

and

Endiandra

(Lauraceae), and

Elaeocarpus

(Elaeocarpaceae)

5 10 11

. Occasionally a single species may achieve local dominance, for example

![]() Lindsayomyrtus racemoides

(Daintree penda) in places at low elevations. Strangler figs (

Ficus

spp.) are rather abundant. They belong to the “keystone species” in rainforests throughout the tropics as different

Ficus

spp. offer fruits throughout the year

12

.

Lindsayomyrtus racemoides

(Daintree penda) in places at low elevations. Strangler figs (

Ficus

spp.) are rather abundant. They belong to the “keystone species” in rainforests throughout the tropics as different

Ficus

spp. offer fruits throughout the year

12

.

![]() Xanthostemon chrysanthus

(golden penda) is common along watercourses. Distinct patches of fire-dependent forest, composed of trees like

Corymbia intermedia

(pink bloodwood) and

Eucalyptus tereticornis

(red gum), occur throughout the area; the boundaries between these patches and closed rainforest are sharp, commonly with ecotones of only a few metres

13

. Well developed mangrove forest occurs near the mouths of the rivers and in sheltered bays

14

.

Xanthostemon chrysanthus

(golden penda) is common along watercourses. Distinct patches of fire-dependent forest, composed of trees like

Corymbia intermedia

(pink bloodwood) and

Eucalyptus tereticornis

(red gum), occur throughout the area; the boundaries between these patches and closed rainforest are sharp, commonly with ecotones of only a few metres

13

. Well developed mangrove forest occurs near the mouths of the rivers and in sheltered bays

14

.

Tropical cyclones (=hurricanes) are the major intensive disturbance agent, and few areas of Queensland rainforest escape storm damage for more than 40 years

15

. Cyclone associated rainfall intensity in this area ranks among the world’s highest. There are fewer rain days but higher mean daily intensities than in most other tropical rainforests. The high rain intensities – together with low subsoil permeability

16

and steep slopes – result in globally exceptional run-off volumes (even exceeding 50 % of the volume of a single storm) which in turn result in considerable nutrient transfer.

17

Annual rainfall is approx. 2000–4000 mm but there is a rather dry period of several months in “winter”

14

. Thus, only a few wetter locations, e.g. Cape Tribulation area in Daintree National Park, can be defined as Moist Rainforest, while most of Wet Tropics is better defined as Evergreen Seasonal Rainforest

7

. Average annual temperature at the coast is approx. 25°C

14

. Winter temperatures are pleasant.

Abundant feral pigs are a great problem; their diggings can be seen everywhere. Population control is very difficult due to the inaccessibility of the forests. 18

Off-trail hiking is rather difficult. Cyclone damage to the canopy results in a dense tangle of thorny rattan palm vines (

Calamus

spp.)

15

. In addition, most of the park has steep topography. However, on flat terrain under closed canopy, progress is easy. Note that despite the claims on the www-sites of both the park and the world heritage site, there is only one overnight hiking route in Daintree National Park, a two-nighter; and even that is almost unused and poorly marked. The rangers are unwilling to give permits for camping outside designated sites. Longer hikes are possible in neighbouring areas, e.g. in

![]() Monkhouse Timber Reserve

.

Monkhouse Timber Reserve

.

References:

1 Stork, N. E. (2005): The Theory and Practice of Planning for Long-Term Conservation of Biodiversity in the Wet Tropics Rainforests of Australia. In Bermingham, E., Dick, C. W. & Moritz, C. (eds.): Tropical Rainforests, Past, Present, and Future . The University of Chicago Press.

2 Flood, J. (1995): Archaeology of the dreamtime. Angus and Robertson.

3 Hyland, B. P. M., Whiffin, T., Christophel, D. C., Gray, B. & Elick, R. W. (2003): Australian Tropical Rain Forest Plants. Trees, Shrubs and Vines. CSIRO. CD-ROM.

4 Nicholson, D. I., Henry, N. B. & Rudder, J. (1988): Stand changes in north Queensland rainforests. Proc. Ecol. Soc. Aust. 15 : 61 – 80.

5 Laidlaw, M., Kitching, R., Goodall, K., Small, A. & Stork, N. (2007): Temporal and spatial variation in an Australian tropical rainforest. Austral Ecology 32 , 10-20.

6 Connell, H. C., Debski, I., Gehring, C. A., Goldwasser, L., Green, P. T., Harms, K. E., Juniper, P. & Theimer, T. C. (2005): Dynamics of Seedling Recruitment in an Australian Tropical Rainforest. In Bermingham, E., Dick, C. W. & Moritz, C. (eds.): Tropical Rainforests, Past, Present, and Future . The University of Chicago Press.

7 Richards, P. W. (1996): The Tropical Rain Forest. Cambridge.

8 Hilbert, D. W. (2008): The Dynamic Forest Landscape of the Australian Wet Tropics: Present, Past and Future. In Stork, N. E. & Turton, S. M. (eds.): Living in a Dynamic Tropical Forest Landscape . Blackwell.

9 West, P. W., Stocker, G. C. & Unwin, G. L. (1988): Environmental relationships and floristic and structural change in some unlogged tropical rainforest plots of north Queensland. Proc. Ecol. Soc. Aust. 15 : 49–60.

10 Graham, A. W. (ed.) 2006: The CSIRO Rainforest Permanent Plots of North Queensland: Site, Structural, Floristic and Edaphic Descriptions. Cooperative Research Centre for Tropical Rainforest Ecology and Management.

11 http://www.derm.qld.gov.au/

12 Laman, T. G. (2004): Strangler fig trees: Demons or heroes of the canopy. In Lowman, M. D. & Rinker, H. B. (eds.): Forest Canopies, second edition . Elsevier.

13

Warman, L. (2011):

![]() Two systems or one?

Vegetation dynamics in

Australia’s

Wet Tropics

.

Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy.

University

of New South Wales

.

Two systems or one?

Vegetation dynamics in

Australia’s

Wet Tropics

.

Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy.

University

of New South Wales

.

14 Tracey, J. G. (1982): The Vegetation of the Humid Tropical Region of North Queensland. CSIRO.

15 Adam, P. (1992): Australian Rainforests. Oxford.

16 Bonell, M., Cassells, D. S. & Gilmour, D. A. (1983): Vertical soil water movement in a tropical rainforest catchment in northeast Queensland. Earth Surf. Proc. Landf. 8 : 253–73.

17 Bonell, M. & Callaghan, J. (2008): The Synoptic Meteorology of High Rainfalls and the Storm Run-off response in the Wet Tropics. In Stork, N. E. & Turton, S. M. (eds.): Living in a Dynamic Tropical Forest Landscape . Blackwell.

18 Congdon, B. C. & Harrison, D. A. (2008): Vertebrate Pests of the Wet Tropics Bioregion: Current Status and Future Trends. In Stork, N. E. & Turton, S. M. (eds.): Living in a Dynamic Tropical Forest Landscape . Blackwell.

Official sites:

http://www.nprsr.qld.gov.au/parks/daintree/

http://www.wettropics.gov.au/

-

-

Syzygium wesa (white Eungella gum), left, with reddish trunk; Aceratium megalospermum (carabeen), right centre, with strongly fluted trunk; the big tree, centre (not identified), with strangling fig ( Ficus sp.); Medicosma fareana (white aspen), the pale trunk between S. wesa and the fig. Elev. 420 m.

-

-

Big tree is Ficus virens (mountain fig, one of the strangling fig species), behind Lindsayomyrtus racemoides (Daintree penda, slender trunk and foliage). Elev. 120 m.