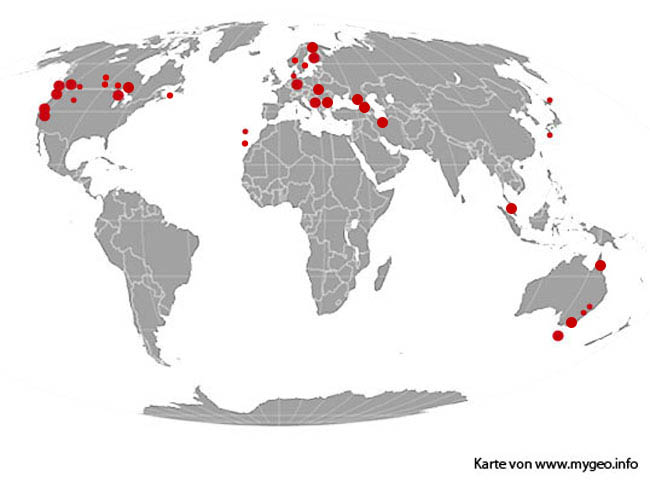

- AUSTRALIA: NEW SOUTH WALES

- AUSTRALIA: QUEENSLAND

- AUSTRALIA: TASMANIA

- Evercreech Forest Reserve

- Franklin-Gordon Wild Rivers National Park

- Lower Coles Road

- McDougall’s Road

- Reynold Falls Nature Recreation Area

- Styx Tall Trees Forest Reserve

- Tarkine

- AUSTRALIA: VICTORIA

- AUSTRIA

- BOSNIA-HERZEGOVINA

- BULGARIA

- Baiuvi dupki-Dzhindzhiritsa Nature ReserveNEW

- Boatin Strict Nature Reserve - NEW !!

- Dzhendema Strict Nature Reserve - NEW !!

- Parangalitsa Strict Nature Reserve - NEW !!

- Rila Monastery Forest Reserve - NEW !!

- Steneto Strict Nature Reserve - NEW !!

- CANADA: ALBERTA

- CANADA: BRITISH COLUMBIA

- Carmanah Walbran Provincial Park

- Clayoquot Sound Biosphere Reserve

- Glacier National Park

- MacMillan Provincial Park

- Pacific Rim National Park Reserve

- Yoho National Park

- CANADA: NOVA SCOTIA

- CANADA: ONTARIO

- Lake Superior Provincial Park

- Michipicoten parks

- Quetico Provincial Park

- Rainbow Falls Provincial Park

- CANADA: SASKATCHEWAN

- CROATIA

- CZECHIA

- DENMARK

- FINLAND

- Helvetinjärvi National Park

- Isojärvi National Park

- Kurjenrahka National Park

- Patvinsuo National Park

- Petkeljärvi National Park

- Pyhä-Häkki National Park

- Urho Kekkonen National Park

- Vätsäri Wilderness Area

- GEORGIA

- GERMANY

- Bavarian Forest National Park

- Fauler Ort Nature Reserve

- Hainich National Park

- Harz National Park

- Heilige Hallen Nature Reserve

- Jasmund National Park

- Müritz National Park

- Rhön Biosphere Reserve

- IRAN

- JAPAN

- MONTENEGRO

- PORTUGAL

- ROMANIA

- SLOVAKIA

- Boky National Nature Reserve

- Dobroč National Nature Reserve

- Havešová National Nature Reserve

- Stužica National Nature Reserve

- SPAIN

- SWEDEN

- UNITED STATES: CALIFORNIA

- Humboldt Redwoods State Park

- Kings Canyon National Park

- Mokelumne Wilderness

- Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park

- Sequoia National Park

- Yosemite National Park

- UNITED STATES: MICHIGAN

- UNITED STATES: WASHINGTON

- Goat Marsh Research Natural Area

- Mount Rainier National Park

- Olympic National Forest

- Olympic National Park

- UNITED STATES: WYOMING

Quetico Provincial Park, Ontario, Canada

Quetico (4760 km 2 ) and the adjacent Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (BWCAW, 4400 km 2 ) across the border in Minnesota together form a huge protected area. Thousands of clean-water lakes, lovely small rivers, no motorboats, no cottages and no logging – a canoeist’s paradise! After a long battle, a logging ban came into effect in 1973 in Quetico 1 and in 1978 in the BWCAW 2 . 1500–2000 km 2 of virgin forest remained in Quetico 3 and 1520 km 2 in the BWCAW 4 . Unfortunately, there is no map of the virgin forest areas of Quetico, the earlier logged areas being apparently not documented well enough, but a 971 km 2 tract 5 known as Hunter Island (not a true island) is almost totally untouched 3 . For the BWCAW there are accurate maps of unlogged areas. Much of the land had probably not even been penetrated by indigenous people, for their numbers were small and they stayed close to the water routes 6 .

The park lies at approx. 400 metres of elevation on the Canadian Shield. In the majority of Quetico, the bedrock is granitic, and soils thin and low in nutrients; consequently, the productivity is low. There are small areas of metamorphic, sedimentary and volcanic rocks; forests on these bedrocks are more productive and diverse. Average annual precipitation is 744 mm and average annual temperature 2.0°C. 5

The park is in the transitional zone between the temperate deciduous forests to the south and the boreal forests to the north but so close to the northern limit of the zone that the vegetation is overwhelmingly boreal in nature

7

. However, there are southern elements, more or less rare, which point to the temperate zone, like

Acer

(maples),

Quercus

(oaks),

![]() Fraxinus pennsylvanica

(red ash),

Fraxinus pennsylvanica

(red ash),

![]() Populus grandidentata

(large-tooth aspen) and

Populus grandidentata

(large-tooth aspen) and

![]() Betula alleghaniensis

(yellow birch).

Betula alleghaniensis

(yellow birch).

![]() Pinus banksiana

(jack pine) is the most important tree, followed by

Pinus banksiana

(jack pine) is the most important tree, followed by

![]() Picea mariana

(black spruce)

7

.

Picea mariana

(black spruce)

7

.

![]() Populus tremuloides

(quaking aspen) and

Populus tremuloides

(quaking aspen) and

![]() Betula papyrifera

(paper birch) are very abundant, too

5

.

Betula papyrifera

(paper birch) are very abundant, too

5

.

![]() Pinus strobus

(eastern white pine) and

Pinus strobus

(eastern white pine) and

![]() Pinus resinosa

(red pine) often grow on the shorelines, therefore appearing to a paddler to be more abundant than is actually the case

5

. Together these species comprise about 8% of the forested areas

7

but about 25% prior to logging and fire suppression (the best

P. strobus

–

P. resinosa

forests were logged first)

2

. Treed bogs are dominated by

P. mariana

5

. In all, there are more than 30 tree species

7

. Most are easy to identify but e.g.

Pinus resinosa

(red pine) often grow on the shorelines, therefore appearing to a paddler to be more abundant than is actually the case

5

. Together these species comprise about 8% of the forested areas

7

but about 25% prior to logging and fire suppression (the best

P. strobus

–

P. resinosa

forests were logged first)

2

. Treed bogs are dominated by

P. mariana

5

. In all, there are more than 30 tree species

7

. Most are easy to identify but e.g.

![]() Sorbus americana

(American mountain-ash) and

Sorbus americana

(American mountain-ash) and

![]() S. decora

(showy mountain-ash) may be difficult to tell apart.

S. decora

(showy mountain-ash) may be difficult to tell apart.

The natural fire cycle is approx. 70–80 years

5

. Between 1940 and 1976, the period of effective fire suppression, there were very few fires

1

. Today, some fires initiated by lightning are allowed to burn; the estimated fire interval today is about 300 years

5

. Running crown fires, which burned the most area before fire suppression, are not allowed to develop

2

. Due to the scarcity of wildfires in recent decades, shade-tolerant and fire-sensitive

![]() Abies balsamea

(balsam fir) is now very common in the understory

2

. All the main tree species are well-adapted to fires:

P. banksiana

and

P. mariana

have serotinous cones, which shed their seeds after fire has killed the parent trees, producing extremely dense regeneration,

P. tremuloides

reproduce prolifically from root suckers,

B. papyrifera

sprouts from stumps and reproduce from light seeds

8

, and

P. strobus

and

P. resinosa

have fire-resistant bark

2

.

Abies balsamea

(balsam fir) is now very common in the understory

2

. All the main tree species are well-adapted to fires:

P. banksiana

and

P. mariana

have serotinous cones, which shed their seeds after fire has killed the parent trees, producing extremely dense regeneration,

P. tremuloides

reproduce prolifically from root suckers,

B. papyrifera

sprouts from stumps and reproduce from light seeds

8

, and

P. strobus

and

P. resinosa

have fire-resistant bark

2

.

Apart from a few short ones at the northern boundary, there are no hiking trails, most of the park being accessible only by canoe. Hiking in the forest is hard: in older forests there is dense

A. balsamea

regeneration almost everywhere, fallen trunks derived from post-fire dense

P. banksiana

and

P. mariana

regeneration are numerous and bogs are common, too. The heaviest use is in the southern sector by American canoeists arriving directly from the BWCAW; in the north, the heaviest use is in the sector accessible from French Lake

5

. Almost nobody goes from the shorelines far into the forest. The period with the heaviest use is July 25 to August 15

9

. Compared to the BWCAW, Quetico is somewhat wilder with no hunting, more fires in the 1900’s

2

, more stringent quotas, no latrines, no fire grates and no designated campsites

1

. In contrast to the BWCAW, camping is allowed anywhere in Quetico. Although motor vehicles are prohibited in the park, you cannot escape

motor

noise: a lot of scheduled flights go over the park and at least in the summer peak period there are many small aircraft, too (landing is prohibited).

References:

1 Nelson, J. (2009): Quetico, Near to Nature’s Heart. Natural Heritage Books.

2 Heinselman, M. (1996): The Boundary Waters wilderness ecosystem. University of Minnesota Press.

3 Frelich, L. Pers. comm. (2008)

4 Frelich, L. (1995): Old Forest in the Lake States Today and Before European Settlement. Natural Areas Journal 15 : 157-67.

5 Quetico Background Information. 2007. Ontario Parks.

6 Ahlgren , C. & Ahlgren , I. (1984): Lob Trees in the Wilderness. University of Minnesota Press.

7 Walshe, S. (1980): Plants of Quetico and the Ontario Shield. University of Toronto Press.

8 Agee, J. K. (1998): Fire and pine ecosystems. In Richardson, D. M. (ed.): Ecology and Biogeography of Pinus . Cambridge University Press.

9 Clark, J., Canoe Canada Outfitters. Pers. comm. (2013)

Official site:

http://www.ontarioparks.com/park/quetico

-

-

Pinus resinosa (red pine) stand at Elisabeth Lake. Also Sorbus decora (showy mountain-ash) seedling, bottom; Pinus strobus (eastern white pine) seedling, bottom centre; Abies balsamea (balsam fir) seedlings, bottom left and background.

-

-

Fred Lake. Mainly Pinus banksiana (jack pine) and Picea mariana (black spruce, narrow crowns). Also a few wide crowns of Pinus strobus (eastern white pine), background.

-

-

Picea mariana (black spruce) dominated forest. Also a thicker Pinus banksiana (jack pine, left), Betula papyrifera (paper birch, right foreground) and small Abies balsamea (balsam fir, right centre).

-

-

Old-growth Pinus stand at Sturgeon Lake with P. strobus (eastern white pine, with long horizontal branches) and P. resinosa (red pine, other tall trees). Fraxinus pennsylvanica (red ash) along the shore.

-

-

Fraxinus nigra (black ash, dark trunks) - Betula papyrifera (paper birch, white trunks) forest along a small creek. Also a small Ulmus americana (American elm, left centre).

-

-

Fraxinus nigra (black ash), also background and foliage top left. Acer spicatum (mountain maple) foliage top right.

-

-

Fraxinus nigra (black ash) stand. Also white trunks of Betula papyrifera (paper birch, extreme left), Picea glauca (white spruce) and small Ulmus americana (American elm, left and right centre).

-

-

Allan Creek. In the wetland Pinus banksiana (jack pine) and Larix laricina (tamarack larch, sparse narrow crowns, left).

-

-

Stunted Pinus resinosa (red pine) at unnamed small lake. Two small Pinus banksiana (jack pine), bottom right. The same species in the background, P. resinosa with long needles.